Crop Genomics

Our Lab is using new generation sequencing platforms including Illumina, PacBio, and comparative-genomics methods to study the crop genomes. We have accomplished several projects and still been working on several new genomes, including:

-

Assembly and annotation of Zoysiagrass (结缕草;Zoysia japonica Steud.)

Zoysia is a genus of creeping grasses widespread across much of Asia as well as Australia and various islands in the Pacific. Because they can tolerate wide variations in temperature, sunlight, and water, zoysia are widely used for lawns in temperate climates. They are used on golf courses to create fairways and teeing areas. Zoysia grasses stop erosion on slopes, and are excellent at repelling weeds throughout the year. They resist disease and hold up well under traffic (From WikiPedia).

In collaboration with Prof. Kehua Wang at CAU, and the Wuhan Biotechnology Institute, we are using the third generation sequencing technology to sequence and annotate the genome of Zoysia (genome size 421 Mb). We have generated 15 Gb PacBio reads (40x coverage for the initial assembly). The aim is to identify the genes involved in tolerating environmental stress, which can be used for grass breeding and genetic improvement.

-

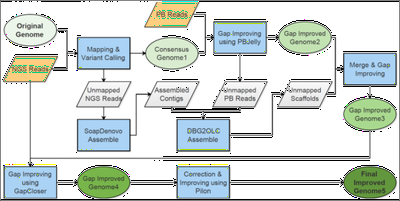

Single-molecule sequencing of wild and cultivated African rice

The single-molecule real-time (SMRT) sequencing platform presented by Pacific Biosciences (PacBio) is regarded as a third-generation sequencing technology. In this work, we combined PacBio (∼15x) with Illumina reads (∼40x) to improve the genome assemblies of African wild (Oryza barthii) and cultivated rice (O. glaberrima), and to infer large structural variations (SVs) between O. barthii and O. glaberrima. We developed a pipeline for mixed assembly of a genome with Illumina and PacBio reads, as illustrated below, including a series of tools: BWA, SAMtools, PBcR, PBsuite, PBjelly, SOAPdenovo, GapCloser, DBG2OLC, PILON (Figure 1). We also identified hundreds of large structural variations based on PacBio reads, including an interested region that may contribute to the domestication of the prostrate trait during the evolution from wild rice to cultivated rice in Africa. Because this region is very long (~40 Kb), it might have been overlooked by Illumina sequencing (Figure 2). This work is published in Molecular Plant (2016).

Figure 1. The pipeline for a mixed assembly of the African rice genomes.

Figure 2. A 37.2-kb deleted fragment containing six protein-coding genes from O. glaberrima chromosome 3 -

Impact of retrotransposon activity and genome size evolution in plants

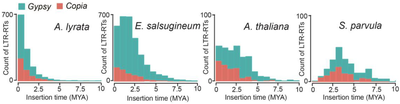

Dynamic activity of transposable elements contributes to the vast diversity of genome size and architecture of plants. We examined the genomic distribution and transposition activity of long terminal repeat retrotransposons (LTR-RTs) in Arabidopsis thaliana and three of its close relatives, Arabidopsis lyrata, Eutrema salsugineum and Schrenkiella parvula, in Brassicaceae. Our analyses revealed distinct evolutionary dynamics of Gypsy retrotransposons, which reflects different patterns of genome size changes of the four species over the past million years. The rate of Gypsy transposition in A. lyrata is approximately five times more active than that in A. thaliana and E. salsugineum, suggesting an expanding A. lyrata genome. Gypsy insertions in E. salsugineum are strictly confined to pericentromeric heterochromatin, showing a correlation with a dramatic centromere expansion. In contrast, these elements in S. parvula have been largely suppressed over the last million years, likely a result of an inherent mechanism of preferential DNA removal on Gypsy elements. Additionally, species-specific clades of Gypsy elements shaped the distinct genome architectures of A. lyrata and E. salsugineum (Manuscript submitted).

Figure 1. Distribution of insertion times of Copia and Gypsy retro-elements in the four species